Beyond the Guacamole: The true story of Mexico’s green gold

Traditional Mexican food is made from native and pre-Hispanic ingredients that sprouted from its land thousands of years ago. Among them, there is one that is still as important today as it was for its ancestors. A delicacy, which the Aztecs conferred aphrodisiac properties: the avocado; one of the gods of Mexican food. The absence of this ingredient makes any dish naked and incomplete. Due to the abundance of this fruit in nature, traditionally, its presence on the plate was never spared – until now.

Nowadays, the national avocado industry has taken a dark path that receives very little attention from its new international consumers who have added this fruit to their daily diet. The avocado has not only become a luxury product with international prices unattainable for most Mexicans, but what most of its international consumers don’t know is that the Mexican avocado has become a hostage of the drug trafficking cartels. In this post, I will explore the phenomenon of the international avocado boom and the multi-dimensional impacts that its popularity is having in Mexico.

Tree Testicle

They say that the first avocado was discovered in a cave in Coxcatlán Puebla 10.000 BC. Its name comes from Nahuatl* “ahuacatl”, which means “tree testicles” because of the shape of the fruit. The tree, also known as “tree of the generation of life”, was considered sacred.

Avocado is an ecological, cultural and culinary pride of Mexico; a gift from the land that is celebrated every day, with every meal. This deep relationship and history with the fruit has made Mexico the largest avocado producer in the world. In this last decade, its popularity has exploded globally. Mexico produces one-third of the avocados consumed globally. In the year 2000, 900 thousand tons of avocado were produced, and in 2018 this figure rose to 2 million tons.

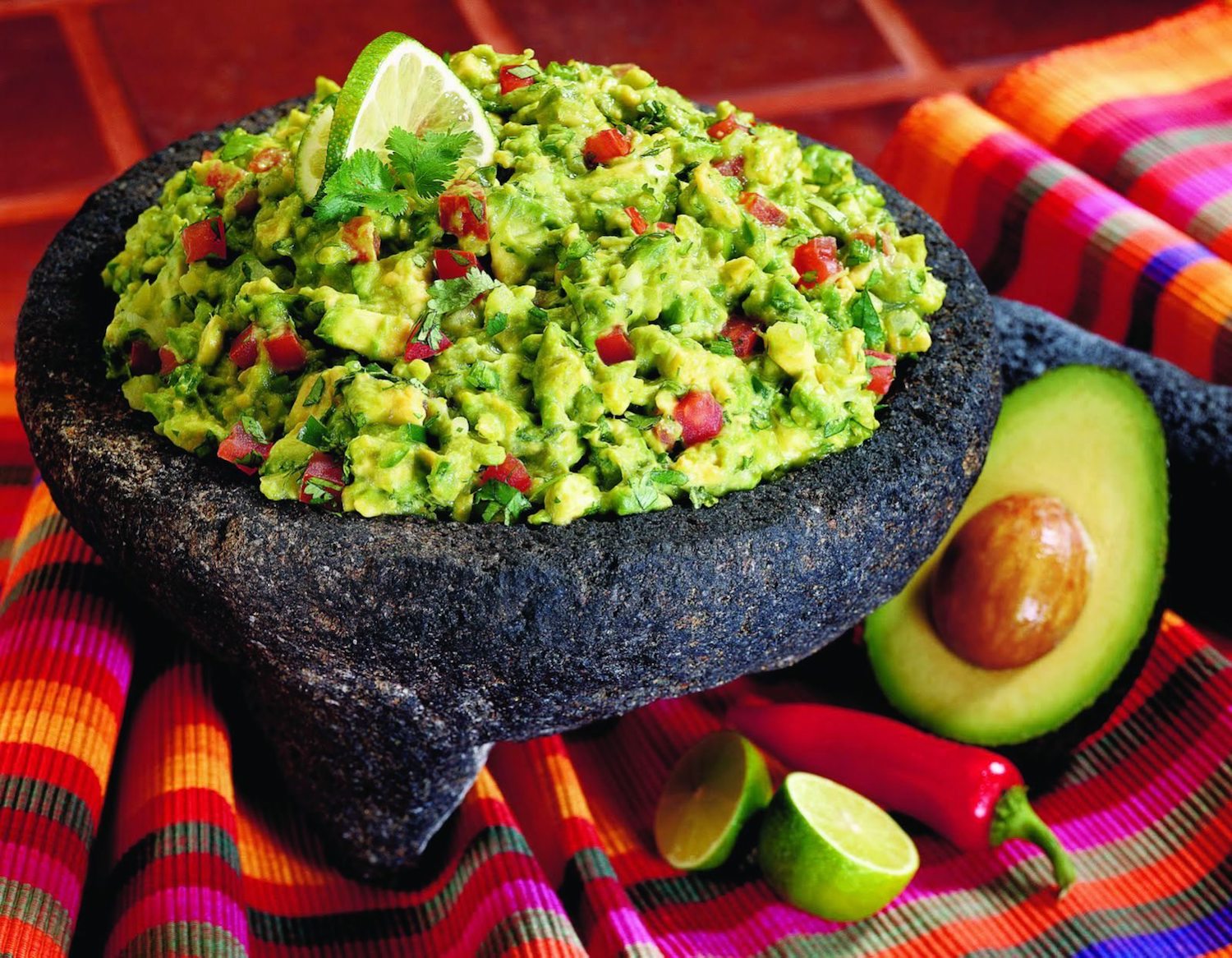

This boom has something to do with improvements in the distribution methods that have facilitated the fruit to arrive green at its destination. Its popularity has also partly increased due to healthy food trends in the global North which has led to a demand for natural sources of “good fats” as part of a healthy diet. However, it is said that the avocado industry in Mexico exploded as a result of the strong campaign launched by avocado farmers in California in the 90s, who commercialized guacamole as a “snack” food to eat while watching American football games. From the success of this campaign onwards, the United States became the largest importer of avocados in the world. Today, this avocado fever has spread globally to such an extent that the obsession with the fruit is creating new traditions and inventing new “functions” in very curious ways.

Avo-Trends

The famous “avocado toast” is a piece of toasted bread with avocado sliced on top. Despite its simplicity, the most Instagrammed “dish” on the Internet has become an epidemic perhaps even larger than the avocado itself.

The famous “avocado toast” is a piece of toasted bread with avocado sliced on top. Despite its simplicity, the most Instagrammed “dish” on the Internet has become an epidemic perhaps even larger than the avocado itself.

The Avocado Show is a restaurant in Amsterdam that has made avocado the star ingredient of all its dishes. All the plates are presented in a very artistic way, making the meal look like a painting or sculpture made with food. Their famous Avo-Burger uses an entire avocado to replace the bread bun. The restaurant is so popular that there is always a long line outside, and they recently opened a second branch in Brussels.

Other restaurants with the same approach have emerged. Among them, there is Avocaderia in New York, Avobar in London, and Avocado Grill in Florida. A cafe in Melbourne Australia took it even further by inventing the “avolatte”; coffee lattes served inside the shell of an avocado.

What is happening with the avocado today follows the same trajectory as many other products that have been absorbed into the international market. Globalization markets the traditional food of countries of the global south as the new fashionable health product, a “superfood” that will make you live 10 more years if you consume it every day. This may be great for most people who now enjoy a new and delicious exotic product at low cost and perhaps also good news for the national economy of the exporting country, but not so fortunate are the citizens who now have to pay double for a staple food item of their diet.

The Colonization of the Avocado

The United States purchases 77% of the Mexican avocado which makes up 91% of the avocado imported into the United States. The high season of guacamole consumption in the US is during the Super Bowl. It is said that more than 105 million pounds (48 million kilograms) of avocado are consumed on the Sunday of the big game.

This “custom” presents an example of how modern traditions are created based on the economic opportunities of a capitalist system. The avocado marketing in the US found its niche; as you can see in this video of US-American humor that promotes the consumption of “Avocados from Mexico” specifically during the game of American football.

This 30-second video reveals many things about the “avocado-boom” phenomenon. For just this short television broadcast, this commercial cost an alarming 4 million dollars. The commercial demonstrates the important role played by advertisement because it is clear that they really work.

I would like to draw attention to the phrase that is used in the video; “Come and get them, hipsters.” The Western association that consuming avocado classifies you as a “hipster” is a modern-day stereotype which I find quite puzzling. I eat avocados because I grew up eating them and they are delicious, not because it is “fashionable.”

Thanks to globalization, native products from every corner of the world now have the opportunity to be known by anyone. As this process unfolds, however, I find it very disappointing when certain traditional products are stripped of their culture and their history upon arrival at their new destination. Because new consumers cannot relate to their original traditions, rather than honoring their origin, they invent “new traditions” and labels.

I do not argue that there is something wrong with adopting a foreign product, using it, inventing new and modern recipes, or doing whatever one wants with that product. Indeed, that is the beauty of globalization; the opportunity it offers us to access new cultures and traditions. However, re-classifying a product that has deep historical and cultural roots is disrespectful to the mother culture of the product. More than 500 years ago the Aztecs used guacamole as a dressing. To say that guacamole is an American Super Bowl tradition is historically dishonest and a huge disrespect to the roots of Mexican culture, besides a huge appropriation of culinary traditions.

Similar was the fate of the quinoa after the international market got its hands on it. When the world discovered the nutritional properties of this cereal, demand and price skyrocketed. Quinoa has been a staple food for Andean indigenous people for generations, and it is now too expensive for many of them to eat. One of the downsides of food globalization is that the market (and its consumers) do not consider that these foods have become inaccessible to the very people who created their tradition and history.

The international popularity of avocado has had a great economic impact on its national prices. According to the Ministry of Rural Development of Mexico, between 2012 and 2017 there was an increase of 584% in the value of exports. Fifteen years ago in Mexico, one kilo of avocado cost only 5 pesos (€.23), today it can sell up to 95 pesos (€4.33) – making it a luxury product. The production that remains for consumption in Mexico is decreasing. If prices continue to rise, the impact this would have on popular Mexican traditions is worrisome. It is this increment in the economic value of the fruit that has given avocados the nickname; Mexico’s green gold.

Environmental Impact

The state of Michoacán contributes more than 80% of the total export of avocado produced in Mexico. In the year 2000, Michoacán had 100 thousand hectares of avocado, today it is estimated that there are 200 thousand hectares.

This huge increase in production has been achieved through illegal deforestation that has displaced an enormous forest area. The serious environmental impacts that this is having in the region are already effecting natural systems. The intensity of the monoculture and the construction of more than 50 thousand water wells are interrupting the water cycle by preventing the capture and filtration of water. These impacts on the hydrological cycle are increasing the demand for water to sustain the intensity of the crop, which results in the lack of water for the surrounding communities.

This excellent French documentary “Avocados from the Devil,” exposes how the Michoacán avocado industry uses agrochemicals and pesticides prohibited by law since their toxicity is highly hazardous to human health. However, they are still well-received by countries that have banned the use of these same chemicals in their own agriculture for decades, as well as the 27 countries of the European Union.

The documentary shows several cases of people who have been affected by exposure to chemicals. Women who suffered abortions during pregnancy, as well as children born with brain retardation, physical deformities, and cancers (particularly blood cancer). Even with a health epidemic among the children of the region, the issue of pesticides is a taboo subject widely ignored by the health services and the authorities due to the important economic role that the avocado has in the Michoacán region. Protecting the stability of avocado production is the priority to safeguard the economic prosperity of the region – at any cost.

The lack of regulation by the authorities is causing tragic impacts on the environment and the health of its citizens. However, greed and institutional corruption are not the only factors that have economic interests in the avocado industry. The region’s drug cartels are also playing an important role in ensuring that the demand and production of this Aztec fruit do not cease.

Avo-Narcos

The Knights Templar are the cartel that has controlled the area of Michoacán for the last decade. The cartels extort avocado farmers by charging them a kind of “tax” for the production as a form of “land right.” It is said that today the cartel has managed to extort money from every person involved in the avocado industry; from the owners of the plantations, the harvesters, and even the fertilizer manufacturers. The same plantations are also used to launder money from drug trafficking. It is said that the farmers are charged one hundred dollars for each hectare cultivated, and ten cents for each kilo produced. Those who refuse to pay are kidnapped or killed. Through these strategies, the cartel earns about 150 million dollars a year.

Faced with the authority’s failure to confront the extortion of the cartels, in 2013 self-defense groups emerged in Michoacán. Using illegal US weapons, these groups of civilians linked to the avocado business took up arms against the Knights Templar. Joining the local police, the self-defense movement began to grow and to protect more people from organized crime. Financed by the same avocado producers, little by little, the “civilian police” was recovering the territory.

Supposedly, much is being done to restore calm in the avocado region, but it is also speculated that members of the self-defense group have allied with other cartels to fight for their part of the avocado cake. The ongoing fight between taking and protecting Mexico’s green gold has made the threat of violence the curse that haunts anybody involved in Michaocan’s avocado industry. Today, the entire avocado zone is monitored 24 hours a day by members of the “civilian police.” There are checkpoints on all the roads leading to the avocado villages to control who enters and leaves the region.

Should the Avocado be Politicized?

The avocado has become an economic miracle for Mexico, particularly for Michoacán. However, the lack of regulation and institutional corruption are causing devastating environmental and social impacts. As long as the avocado market continues on its millionaire trajectory, it is evident these impacts will remain ignored by the authorities. The situation becomes even more complicated under the control of the drug cartels who are fomenting violence in a territory dedicated to agriculture and are turning farmers and civilians into clandestine warriors.

The Mexican people, victims of a political system that ignores their safety and well-being are also confronted with the context of violence inflicted by the drug cartels. This has been the unfortunate Mexican reality of the 21st century. As consumers, how can we help break this vicious circle of violence and injustice that stains the Mexican avocado? Would it help to boycott this Mexican product? Eliminate it from our weekly purchase?

Fortunately, the problematic case of the Mexican avocado has begun making noise throughout the world. Some restaurants in England, such as the Wild Strawberry Cafe, among others, announced that they will stop serving Mexican avocados because of the environmental and social impacts tainting its supply chain. However, it is clear that boycotting the avocado would harm those who depend on the industry, particularly the farmers. Therefore, I don’t believe this is the sole solution.

The complexity of this story produces a crippling lack of answers and solutions. That is why I hope to help spread the dark reality that we are unconsciously financing this problem when we consume the delicious Mexican avocado. In this globalized world, honoring cultural traditions is as important as opening our eyes to the true cost of the products we consume.

Eating with awareness is the goal.

Buen provecho,

Cookie

*Nahuatl is one of the 68 native languages of prehispanic Mexico that are recognized by the Mexican State. It is spoken by the indigenous Nahuas and was the language of the great Aztec empire, so it remains the most important to this day.

**Article re-edited on 2nd of January 2020

Leave a Reply